As the Los Angeles 2028 Olympic qualification period begins, few coaches carry the weight of expectation quite like Driton Kuka. Sitting down for a friendly conversation at the Mittersill Olympic Training Camp, the man who has guided Kosovo to five Olympic medals, including three golds, across three consecutive Games reflects on what it takes to remain at the pinnacle of international judo.

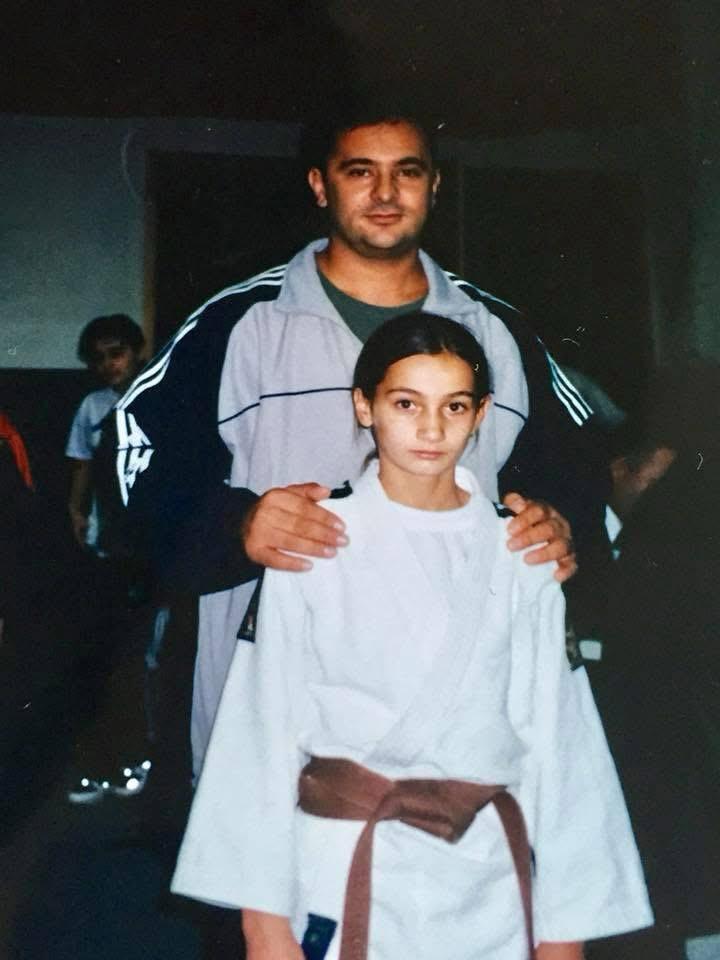

In the first of a three-part series, Kosovo’s head coach Driton Kuka, affectionately known as “Toni”, opens up about his unique coaching philosophy, the sacrifices behind Olympic gold and why building champions from a small nation requires creating a Ferrari from scratch.

“We, as Kosovo, with a small base, with a small number of athletes, we must from one athlete build Ferrari,” Toni explains, his words cutting to the heart of his philosophy. “So it is really hard to make both, normal life and top athlete life.”

This metaphor, building a Ferrari, encapsulates everything about Kuka’s approach. It is meticulous, demanding and uncompromising. Yet, it is also the only way a nation of fewer than two million people has managed to stand alongside judo superpowers on the Olympic podium.

LA2028, here we come…

As we enter the LA2028 qualification period in a few months’ time, Toni is characteristically pragmatic about his team’s prospects. “For the qualification, we have three top athletes who qualified for Paris,” he begins. “We are trying to develop new athletes who have the potential to achieve Olympic qualification. At the moment, we are carrying out some experiments with some of the girls, so to speak. Some of them are moving down a weight category, and we also have some new athletes who were not involved in the Olympic Games in the past.”

His target? Three to five Olympic qualifications. “If these three, Distria, Fazliu and Akil, are in good health, Olympic qualification is certain. In addition, we have three or four young athletes who could be within the qualification pathway for Los Angeles.”

Still, Toni knows better than anyone that Olympic cycles cannot be replicated. The methodology that delivered Majlinda Kelmendi’s gold in Rio 2016 was not going to work for Tokyo, and Tokyo’s approach was not going to suffice for Paris.

“If I compare myself as a coach for Rio, Tokyo and Paris, I think that I have improved myself in each Olympic cycle with new methods, new judo and new approaches.” he reflects. “The Olympic Games are a four-year period and you cannot achieve good results using the same methodologies throughout. This is my experience.”

It is a lesson learned through evolution, adaptation and a substantial commitment to staying ahead of the curve in a sport where global investment continues to accelerate.

The Japanese Connection

One of Toni’s most significant recent decisions has been bringing a Japanese coach into the Kosovo setup, a remarkable choice for a coach who has built his reputation on developing homegrown talent.

“We have a big number of good young athletes,” he explains. “What I see in the work and in the future of these athletes under 18 is that we must improve ne-waza, and this is the reason I spoke with our Federation President and with the Ministry, and it is a project supported by the Ministry.”

The move reflects Toni’s willingness to acknowledge gaps and seek expertise where needed. “Majlinda and the other coaches need the experience and knowledge of a Japanese coach in order to further improve ne-waza. Ne-waza is also a strong part of Nora [Gjakova] as an athlete, so I think that Japanese expertise and Nora’s ne-waza together can greatly improve the younger generation.”

It is a strategic investment in Kosovo’s future, recognising that whilst Toni has mastered the art of building Olympic champions, the next generation will require new tools, new knowledge and perhaps most importantly, fresh perspectives.

The Marathon Ahead

Managing athletes through a two-year qualification cycle is a marathon, not a sprint. How does Toni keep his team mentally fit and emotionally balanced?

“Now we start. Let’s say that from this Mittersill Olympic training camp, we begin to think seriously about all the details,” he says. “It is time to warm up the engines of each athlete, to assess possibilities and injuries. We have already dealt with some problems and now I think the whole team is healthy and ready.”

Still, it is more than physical preparation. “Now it is time to start, to make a really good plan and to establish a strategy first for Olympic qualification and afterwards for our main goal: an Olympic medal. So, now we are in January 2026, two and a half years, let’s say, before the Olympic Games, is the time to set up a clear pathway and a real working system for what we want to achieve.”

By setting clear long-term goals, demanding honesty and discipline, as well as constantly working on the athletes’ mindset, Toni ensures they stay mentally strong, emotionally balanced and focused throughout the long qualification journey.

Whilst we are discussing about LA2028, beneath the strategic planning lies a deeper objective and more responsibilities further ahead. “My goal, as the head coach, is also to build a new team who is following our top athletes also for the Olympic Games 32 and 36.”

A Philosophy Born of Necessity

When asked to distil his coaching philosophy into one sentence, Toni doesn’t hesitate: “Sometimes I tell my athletes not to think with their minds because they will stop. They must just keep going because if you are very tired and you think in a normal way, you cannot do it. So, stop thinking and work until the end.”

It is a philosophy rooted in Kosovo’s reality, a small nation punching far above its weight, where there is no margin for error, no room for mental weakness when physical exhaustion sets in.

As everything in life, this philosophy comes at a cost. When pressed about the hardest part of his job that people don’t see, Toni’s answer is unexpectedly vulnerable.

“The hardest part for me is managing the athletes’ lives as a whole. It is not easy, especially with girls because life goes on. There is always a boundary between how much private life they can have and how much they must be dedicated to high-level achievement.”

He pauses, the weight of his words settling in the room.

“You know…” he pauses again before continuing, “Sometimes I want to impose iron discipline but at other times I feel bad because I also want them to experience life at a young age. This is really hard, because sometimes I say things to them that I do not truly feel in my spirit and heart. Perhaps at times I want them to have more of a life but on the other side I tell them, look, we as Kosovo, with a small base and a small number of athletes, must build a Ferrari from one athlete.”

The Price of Perfection

The internal conflict Toni describes is palpable. He speaks of men wanting to go out, to drink, to stay late into the night. Toni looks intently into space of the room before he says: “Sometimes I need to punish them and I do not feel good about it, because at times I think that this is normal. Perhaps they sometimes need to be free to enjoy one night until the morning.”

“But this is always the problem in myself,” he admits. “Because, as I said before, sometimes I say things to them when I am not even sure myself that I am saying the right things.”

So how does he reconcile this inner turmoil? “When I think about it, these five Olympic medals satisfy me, and even when I have doubts, I come back and count the medals and say, okay, they may have lost something, but they have won a lot. Not only for themselves but for the team, for me, for their families, and most importantly for a young country that many people do not even know where it is.”

He references the impact of Majlinda’s results, followed by Distria [Krasniqi], Nora [Gjakova], Akil [Gjakova], Loriana [Kuka] and Laura [Fazliu]. “Small Kosovo is now a big country through its sporting results and this makes me really happy.”

Decisions That Break Hearts

When asked if he has ever had to make a decision that broke his heart but was right for the athlete or team, Toni’s response is immediate: “Many times…, really, many times. I am fighting with myself over this part of the job because it is a psychological aspect and it is not easy.”

“From the beginning, we have worked as a family and I was not there for them only in judo. Many times, I tried to help them with school, family problems, financial difficulties, life in general, sponsors, or support from the government and the Olympic Committee. Now it is really hard to say things to them that I think are wrong for life but good for their careers.”

He doesn’t know if, years from now, his athletes will say he did right or wrong. “I do not know, it is always a balance of pros and cons with the discipline aspect.”

Then comes a remarkable admission: “Maybe I will start to write important things down, important conversations that we have because this is a very important part for future coaches in the next 10 to 15 years,” he says, smiling, his eyes reflecting on the past while already looking far into the future.

The Generational Shift

Toni sees the challenge facing his assistant coaches, particularly Majlinda Kelmendi, who has transitioned into coaching. “Now I see Majlinda as a young coach. She tries to be as I was but these generations are totally different. And I say to Majlinda, look, do not think that you can do with your athletes what I did with you, Nora and Distria, because time is flying.”

The ‘war generation’, as Toni refers to them, those who were children during Kosovo’s conflict, had a different hunger, a different desire. “Now it is totally different generations. They want 90% life.”

“So now we are trying to find a new way. Always trying a new way,” he continues. “Now I have many conversations with coaches in countries with a higher level of economic development and I ask them to share their experiences because what I did with my three Olympic champions, I cannot do anymore. I must find a new way.”

This, Toni insists, is the challenge for his coaching team. “They must understand that this is 50% of performance: if you manage to make them winners in their minds, champions in their heads, and able to put everything else aside for one main goal. This is not easy. Everybody can play with words. Everybody will say, yes, I will give my 100% but we, as coaches, feel it. Most of them say it but they do not do it. They do not work.”

His frustration is evident. “Sometimes I say to them, come on, you have to start working, and they say, ‘But I am working.’ No, this is nothing. This is 30% of what Majlinda did, 30%. And then they say, ‘Yes, but she is Majlinda.’ They have to remember that she is also a human being. She also had a lot of pain and many difficulties during training but she gritted her teeth and never stopped.”

The Weight of a Nation

Kosovo has won Olympic medals in only one sport across three Olympic Games: judo. All of them have come under Toni’s guidance.

“It is not easy,” he admits when asked how it feels to carry the hope of an entire nation. “Before we go to Olympic Games, they said, oh, no problem. There is Toni with a team and for sure Kosovo will win medals. This is really hard.”

Yet he has reached a point of acceptance. “Now, when I have medals from three Olympic Games, I am really satisfied and even if it happens that we do not win medals at the next Olympic Games, I know that people will say ‘wow’, but come on, it is very normal.”

He puts Kosovo’s achievements in perspective, citing Spain’s 20-year Olympic medal drought in judo. “Imagine Spain as an example, with many clubs, many good coaches and more than 10,000 athletes, and they had to wait four or five Olympic Games for a medal. So, when you see these things, you understand how hard it is to win a medal in judo.”

The pressure, he acknowledges, is immense. “Being the coach of the only team to have won an Olympic medal for the country is really hard. Believe me, it has been 16 years of great stress. Now, sometimes I say to my coaches, come on, take some of this stress on yourselves, because I am already a bit tired of this constant expectation and always having it on my mind.”

To be continued… Stay tuned for “Building a Ferrari” — Episode 2.

Author: Szandra Szogedi